This article originally appeared in the Guardian on May 8, 2019, as part of the Guardian series on Broken Capitalism.

Discontent with America’s economic system is widespread, so could tax credits, transport subsidies, or better childcare help? Or is capitalism not broken at all?

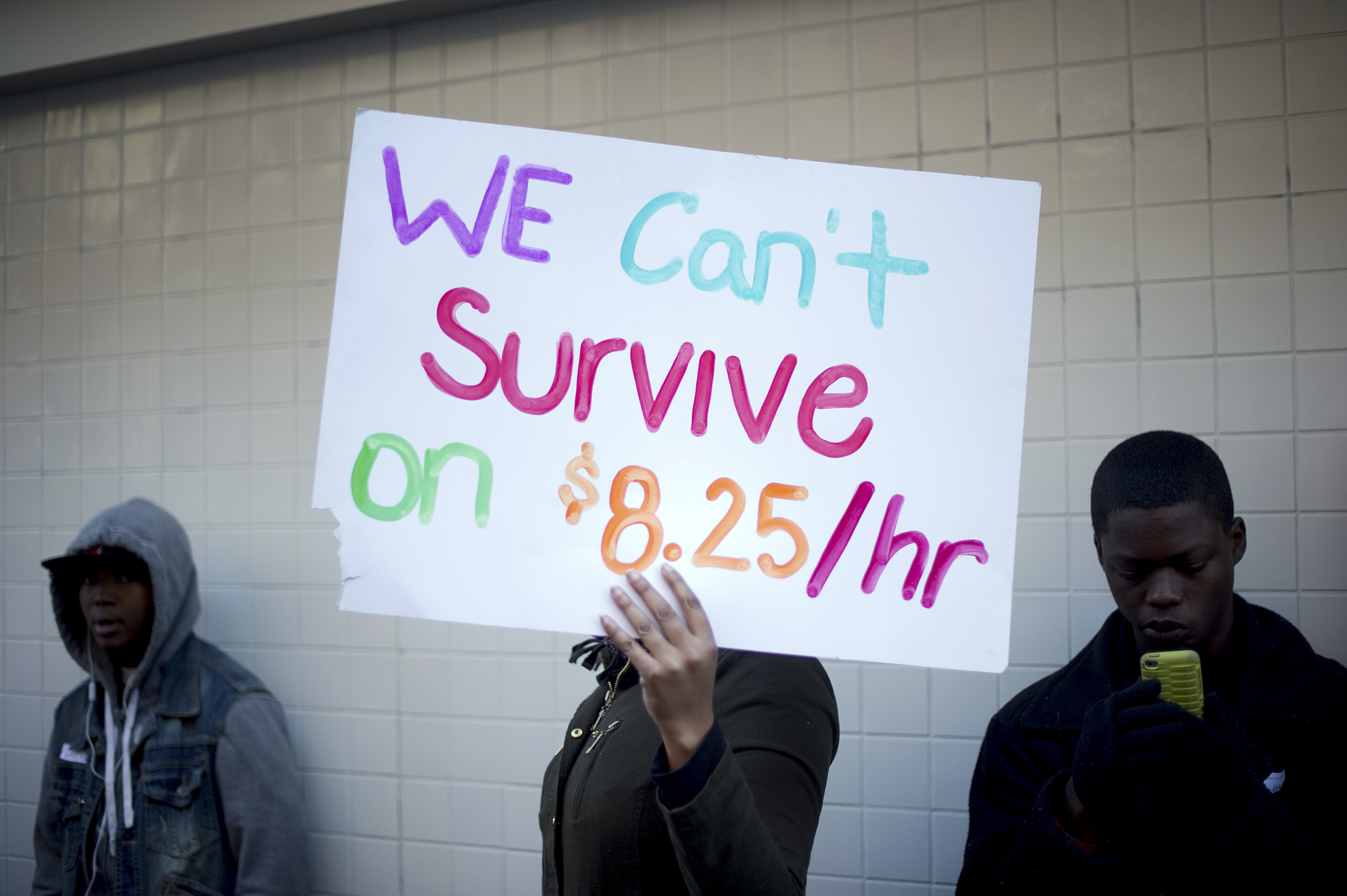

It has been a long time since the typical American worker got a significant increase in pay. Their average hourly or weekly earnings have been stagnant for the past 40 years. It’s time to give them a raise.

One way to do this is to provide a worker tax credit to everyone making less than about $40,000 a year. The idea is to directly subsidize the pay of less-skilled workers, compensating them for the hit they have taken as trade and technology have destroyed well-paid jobs and inhibited wage growth. It would send a signal to these workers that they have not been forgotten, that their contributions to the economy are valuable and deserve to be more adequately rewarded. It would boost employment and encourage marriage. It would give them what they want which is a decently paid job – not welfare.

Yes, it would be expensive. But the alternatives are far worse: declining employment, distressed communities, rising mortality rates, less family stability, rising dependence on disability or other forms of assistance, and the kind of political alienation that elected someone like President Trump.

To be sure, there are other ways to accomplish this objective: raising the minimum wage, encouraging the private sector to share profits with workers, or subsidizing work-related expenses such as childcare. All have merit. So does better education and training to raise productivity and earning power over the longer run. But for now, a worker tax credit is the most direct and visible way to send a signal to lower-paid workers that their contributions are valued and respected.

How would it work? The credit would be equal to 15% of one’s earnings up to a cap of about $15,000 and then phase out gradually above that level. It would be delivered directly to the worker’s paycheck, offsetting payroll taxes and boosting take-home pay. Think of it as negative withholding or a simple adjustment to paychecks similar to what employers already do. Employers would be reimbursed by the Treasury so unlike a higher minimum wage or some other proposals it would cost them nothing. It would instead ask the wealthiest Americans to pay the tab via higher taxes on incomes or wealth.

That top group has enjoyed almost all of the benefits of economic growth. Unless those benefits are more broadly shared, our economic and social divisions will only widen.

So let’s give workers a raise that, unlike President Trump’s promises to this group, will actually improve their lives and sustain democratic capitalism as we have known it.

It’s by now a familiar story: anemic wage growth for most workers and rising inequality have plagued the US labor market since the 1970s, funneling an ever greater share of economic growth to the country’s most affluent people.

What is the most important, foundational action we can take to begin to halt and reverse these trends? It is to stop believing those who claim – falsely – that these trends are the natural outgrowth of a modern economy. An entire industry of economists and other commentators make it their mission to “explain” that rising inequality is the result of natural forces (eg robots!) that increase demand – and wages – for workers with certain types of skills, leaving others behind. This story, unsurprisingly, has major appeal among those who have benefited from rising inequality and do not want to see these trends interrupted. These folks are happy to tout the non-disruptive solution their story implies: workers who don’t want to be left behind should get more education and training.

The problem with this tale? It’s a work of fiction. The hard evidence clearly shows that our increasingly unequal economy is not the inevitable outcome of a modern world, inexorably driven by forces like automation. (And, relatedly, while accelerating the pace at which the US workforce acquires more education and training would help some individuals, it will not put a dent in the issue of rising inequality.)

Only after rejecting the notion that rising inequality is natural and inescapable can we focus on reversing the forces that have been suppressing wages for most workers and thus boosting inequality – namely the deliberate policy choices (either by omission or commission) that have shifted power from workers to their employers.

These include policymakers opting not to increase the minimum wage, allowing its purchasing power to decline over time; turning the manageable challenge of globalization into a deep economic wound for working people via trade agreements that have consistently placed corporate profits over workers’ rights; failing to protect the fundamental right of workers to associate and bargain collectively in the face of ferocious employer assaults on these rights. The list goes on.

The truth is, we have the economy we choose, and in recent decades we have chosen policies that hamstring the bargaining power of working people, channeling economic growth away from workers and toward the wealthy. Rejecting the myth that rising inequality is a foregone conclusion in a modern economy is the first step towards getting to the real work of addressing the policy-driven power imbalances that have resulted in an economy that works for the few and leaves the rest behind.

For most people, a job is a necessary protection against poverty. And employment rates of men – especially among those with less than four years of college – have been declining for 50 years. The rates for women have also been falling since 2000.

The detachment of millions of Americans from paid work has hit rural Americans particularly hard. We need policies that bring “jobs to people”. But we also need to bring “people to jobs”. One way to do this is to subsidize the cost of getting to work. Specifically, I propose a refundable Commuter’s Credit, in a new report from the Aspen Institute’s Economic Strategy Group.

Life without a car is nearly impossible in rural areas, where access to public transportation is all but nonexistent. Things are not much better in many urban areas outside our major metropolitan centers. The second largest expenditure in the budget of a typical US consumer is transportation. This burden is greatest in rural areas.

A Commuter’s Credit would be a transportation subsidy to workers in their first 12 months of employment in a new job. It would be provided through local government employment centers and be available to people who (a) are at least 18 years of age; (b) are unemployed or out of the labor force; and (c) have secured employment offering at least 30 hours per week at the federal minimum wage or higher.

To reduce incentives for short-term job flipping, the credit would be limited to no more than 12 months in any 24-month period. For cost containment, the number of subsidized miles could be capped at 20 per day and $5,000 per year for non-metro residents, and 10 miles per day and $2,500 per year for metro residents. This amount would place the credit on par with the average Earned Income Tax Credit for families with qualifying children; it would also result in a much larger credit for childless workers, providing a much-needed lift to the incentive to work.

With this credit, we can help Americans get work by helping them get to work.

Incomes of American households in the middle and at the bottom of the ladder have grown too slowly for 40 years. The chief culprit: stagnant wages. The nature of modern capitalism, US corporate culture and labor union weakness make this likely to continue.

What is to be done? Raising the minimum wage is good policy, but it benefits mainly those at the very bottom. Some see employee election of corporate board members as a way to compensate for weak unions, but it doesn’t appear to have helped Germany avoid a similar wage problem.

To help a broader swath of workers, we should significantly expand and strengthen the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Right now the EITC provides an average of $2,300 to households with at least one employed adult and modest earnings. With some changes, the EITC could do a lot more to top up wages that are rising slowly, if at all.

First, we should pay the EITC to individuals rather than households. Among other benefits, this will enhance work incentive for second earners.

Second, the EITC should include workers higher up the distribution. The current EITC starts to taper off once earnings reach a certain level and disappears altogether at household earnings of $55,000. We should give every person who earns at least $10,000 the same amount, say $3,500, and raise the earnings cutoff so that about 80% of employed Americans qualify. (This will be especially helpful for workers without children, who currently get only $500.) Extending the reach and generosity of the credit will also ensure the program’s political constituency is rock solid.

Third, the EITC should be increased more each year. Right now, it is indexed to inflation. Let’s instead tie it to GDP per capita, so it can help incomes rise as the economy grows.

An EITC of $3,500 going to the bottom 80% of employed Americans would cost about 2% of GDP, or around $400bn. That is expensive, but we can afford to do it. Given the likelihood that wage stagnation is the new normal, we can scarcely afford not to.

Capitalism is not broken. It does not always work perfectly, of course. But the free market combined with our strong safety net has drastically reduced poverty and improved quality of life for the vast majority of Americans.

A free and healthy economy ensures that wealth is being generated and allocated to those who contribute to its creation. That’s why our current economic health has led to increases in production, and why wage growth for workers in the bottom half of the pay scale is outpacing those in the top half. With unemployment low and labor force participation ticking up, more people are going to enjoy the fruits of a dynamic capitalist economy.

Here’s a big idea – something to keep in mind as you hear about inequality and mobility. The middle class is shrinking, which might make it look like capitalism is failing workers. But the lower class is shrinking, too. Meanwhile, the upper class is bigger than it has ever been. About 28% of households now make more than $100,000 per year, more than double the rate of 40 years ago. More than half of Americans will be part of the top 10% of earners at some point in their lifetimes. Contrary to much contemporary rhetoric, workers in the US are getting richer, not poorer, as competition in the free market allows them to purchase a greater variety of goods for less money than ever before.

To be sure, life is about more than money. Many analysts, from right and left, worry about the tendency of market capitalism to decimate institutions and drain small communities of their vitality. They have a point – the pursuit of economic mobility often entails leaving people, places and ways of life behind.

We should be mindful of how we can support what the supreme court justice Louis Brandeis called the “quality and spiritual value” of local communities. But a free market can provide a solution here, too: employers seeking the best and brightest can and should offer more to employees by way of childcare, skills training and other benefits that help keep families and communities thriving.

And ultimately, each and every individual can and must choose their own path. That isn’t a vice of capitalism – it’s a virtue. A free market is the emergent order of free people, freely making their own decisions. Trying to “fix” that would be badly misguided.

Rumors of the death of mobility have been greatly exaggerated. Capitalism isn’t broken – it’s our best shot at keeping the American Dream of freedom and success alive.

In the United States, access to quality care for children is a pressing concern for the majority of families. It should be a priority for policymakers.

Parents are employed outside the home in nearly 60% of US households with children under the age of 12. This large share stems from two facts. Many US families have two earners, and working single parents have no non-working co-parents at home.

With women’s labor force participation in most European countries approaching or exceeding that in the US, childcare provision is a concern in many parts of the globe. Despite this rise in parents working and the need for childcare usage, data shows that US parents are finding ways to spend more time – not less – with their children. Working parents need access to quality childcare in spite of their time engaging with their children, not instead of it.

Fortunately, decades of research show that well-designed, high-quality childcare programs offer social and economic returns that far exceed their costs. Indeed, high-quality childcare programs offer considerable returns for jurisdictions – large or small – that undertake it. Evaluations of early, high-quality, but small, public pre-school programs found an eightfold social return to dollars invested in such programs.

Studies of recent expansions of pre-school programs to large, statewide populations show that such programs are on track to generate similar returns. Local economic development benefits are a subset of total benefits, but these alone are estimated at $2-$3 per $1 invested.

However, there are important limits to this largely successful track record. Government expansion of childcare has not always improved outcomes for children. Benefits of attending a high-quality early childhood program are largest for children from under-resourced homes. Long-term impacts for children from more resourced families can be small or even negative. Programs that prioritize freeing parents for work outside the home may emphasize childcare availability at the expense of quality.

That’s why successful expansions of childcare access must contain at least two key ingredients: 1) they use curricula and formats demonstrated as high quality and that evaluate innovations rigorously; and 2) they prioritize family and child welfare over narrower goals while considering broad measures of welfare that go beyond adult earnings.

Our children deserve no less, and, actually, much more.

In 1975, the median income for a man with a high school degree supported a family of four at more than twice the poverty line. By 2016, a comparable family cleared the poverty threshold by less than 40%. Just one quarter of young men, aged 25-34, had annual earnings below $30,000 in 1975. By 2016, that figure reached 41%.

A complex range of social and economic factors have driven wages down and workers out. Restoring the labor market to health – not only reversing the trends, but also making up for lost time – will be the work of a generation. But in the short run, policymakers can begin to make progress in the most direct way possible: by putting more money in low-wage paychecks.

The new wage subsidy would work like a reverse payroll tax. Just as every paycheck has a line called “Fica” that makes deductions in proportion to the worker’s earnings, another line called “Work Credit” could add money when the worker’s wage is low. This would operate by setting a target wage of, say, $15 per hour and then paying a subsidy that closes half the gap between the market wage and the target. A paycheck for 40 hours worked at $9 per hour would come with a work credit of $3 per hour, or an extra $120. The subsidy would diminish as a worker’s hourly wage approached $15 and work compensated above the target wage would be unsubsidized.

Such a subsidy would have two major, positive effects. First, it would increase the quantity of work performed by lower-wage workers. Someone who chooses not to work for $9 per hour might accept a job at $12, while an employer who could not employ someone profitably at $12 per hour might gladly do so at $9. Both sides benefit from the subsidy: workers come off the sidelines, and employers build business models more likely to use them. Second, it would increase the price the worker receives for his labor, and thus his take-home pay. Low-income households could more easily make ends meet, via government support that comes tied to work – unlike traditional safety-net benefits that ignore work or discourage it.

America’s long-term goal must be a labor market that offers family-supporting jobs to people of all backgrounds and aptitudes. But the hole dug by decades of misguided policies with regard to regulations, education, trade, immigration, labor and fiscal policy will not be climbed out of quickly. A wage subsidy that encourages reconnection to the labor market and boosts wages at the low end is one policy that can happen right now.

Any defense of the extravagant compensation for corporate executives inevitably boils down to two points: first, it’s fair because it’s tied directly to increased profits and, second, because it provides necessary incentive for these highly talented people to share their excellence and make the often tough decisions necessary to keep their companies competitive.

What’s curious, however, is how infrequently the same logic is used when talking about the pay of frontline employees who actually produce the goods and services sold by their companies.

In the age of “maximized shareholder value”, the corporate view – widely embraced if rarely given voice in public – is that a paycheck at prevailing market wages is all the incentive workers need and all the compensation they deserve. No surprise then that after decades of soaring profits and stagnant wages, American business faces declining employee engagement, loyalty and productivity growth and declining workforce participation.

What’s needed is a new business norm that says all workers should share in the success of their companies, with government playing a supporting role, nudging things in the right direction.

The Securities and Exchange Commission could require public companies in their annual report to calculate how much of their profits are shared with top executives and with frontline workers. And the tax code should reinforce this norm by denying favorable tax treatment to executive compensation and shareholder buybacks unless such a company-wide profit sharing mechanism is in place. Partnerships, small businesses and limited liability corporations that refuse to share profits could be required to forfeit the accounting privilege of passing through their profits to their owners without first paying the corporate tax.

Socialism, you say? Hardly. Giving workers a return on their investment of hard work, talent and loyalty, along with their willingness to risk their economic security on an enterprise, sounds to me like the very essence of capitalism. Granted, it is not the ruthless, selfish capitalism preached by today’s market fundamentalists.

Rather, it is the fair, cooperative capitalism envisioned by Adam Smith, who understood that our own wealth and happiness depends on the wealth and happiness of others.

The rules of our economy and democracy have been captured by a vicious one-two punch.

The first punch lowered taxes at the top – especially capital gains, estate, and marginal income tax – and cut back government regulation; antitrust enforcement; and protections for labor unions. The second punch hit public spending on social welfare on the grounds that it is inherently inefficient. Free-market rhetoric used racialized caricatures like “welfare queens” to demonize government programs as wasteful misallocations of resources to irresponsible.

Our economy rewards those with power. Unchecked power does what it does best: replicates and concentrates.

But now America’s political landscape is shifting. Social movements and labor unions are confronting racial, gender, environmental, and economic injustice head on. We have an opportunity to make a fundamental course-correction.

Progressives can punch back with a one-two counter of their own, as we argue in a Roosevelt Institute report, New Rules for the 21st Century. First, by striking at the heart of plutocracy and breaking up the extreme concentration of wealth, through more robust tax policy and antitrust enforcement, along with corporate governance and labor law reform.

Second, by reimagining interventions as a positive exercises in public power. The role of government reaches far beyond subsides for corporations or market-based interventions. Direct government provision, particularly through public options that can compete away inferior and extractive private options, is the most effective policy.

Public power can be used to spur private sector competition and innovation, and it can also be used to prevent extractive or unjust outcomes. Government power can be used to intentionally foster race and gender inclusion, diminish the divisive premium on social identities, such as “whiteness,” that serve the economic and political interests of the top. This in turn would leave us all, white people included, less vulnerable to the consolidation of economic power we see today.