The way your students approach learning has a large impact on how well they do at school. Thankfully, research shows that teaching your students certain learning strategies helps them to achieve higher results. You can:

Explicitly teach them to your students

Have students use them within your regular lessons

Encourage your students to use them when studying at home

Learning strategies refer to the different things students can do to enhance their learning. There are an endless number of learning strategies. and some are subject or even task-specific. For example, using:

PEEL paragraphs within the body of a essay

Estimates to check the reasonableness of your answer to a mathematical problem

However, some broader learning strategies cut across subjects – and some of these have more impact than others.

Here are seven learning strategies that research shows have a high impact on student learning.

Integrating with Prior Knowledge (elaboration)

Retrieval Practice (retrieval)

Students’ minds are not blank slates. Rather, they contain students’ existing understanding of the world around them. Research shows that students encode information better when they connect it to their existing understandings.

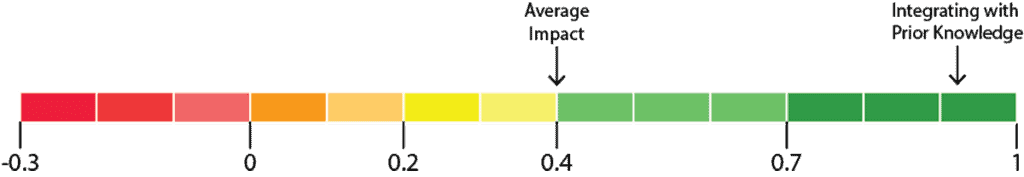

So, the first of the seven learning strategies is integrating with prior knowledge, which researchers sometimes call elaboration. Research shows that students encode information better when they connect it to their existing understandings.

Then, while they engage with new information, teach your students to ask themselves questions such as, how has what I learned:

You need to teach students to ask themselves what they think they know about the topic at hand – before they begin to engage with it.

Confirmed what I already knew?

Added to my existing understanding?

Challenged and changed what I thought I knew?

Distinct from, yet similar to related things?

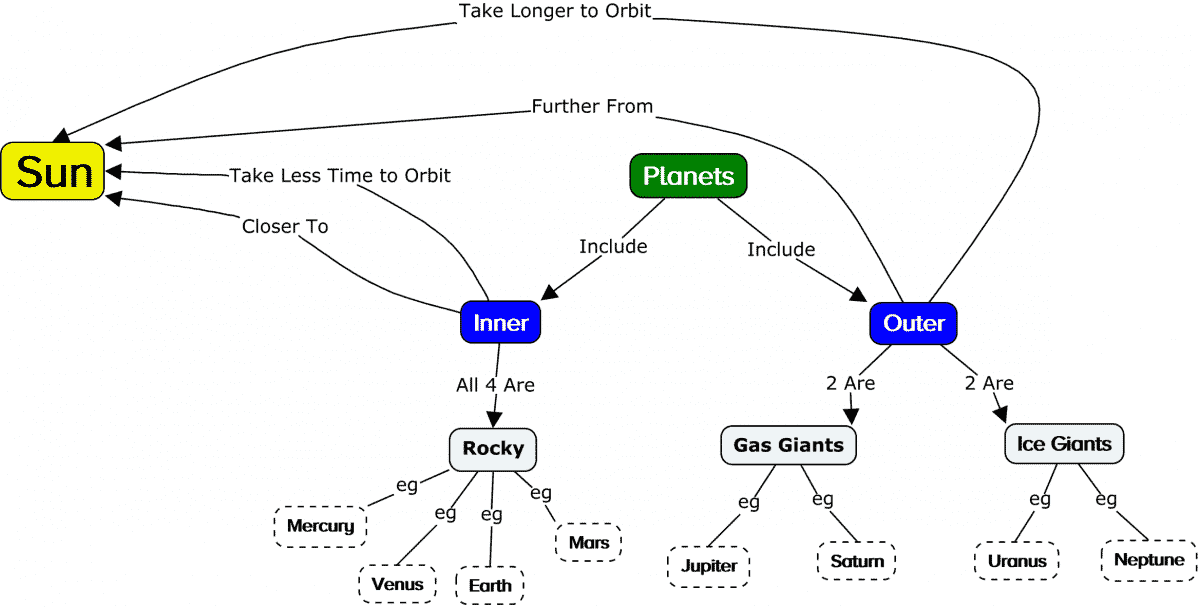

Outlining involves identifying key points and arranging them in an organised way. Students can do this in a range of ways, including:

Using a combination of visuals and words

Note that, to be classed as outlining, the above strategies must focus on extracting key points and leaving out supporting details. These key points can:

Be from a single lesson

Link key ideas from several lessons

Connect key ideas to the students’ personal experiences

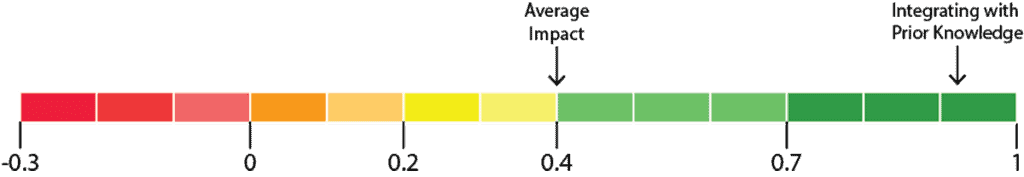

Many of the above strategies have their own set of research behind them (e.g. concept mapping). Yet, research 2 shows the broad strategy of outlining has an effect size of d = 0.85.

While integrating with prior knowledge and outlining help get information into the minds of students, retrieval practice involves students in consciously retrieving information from memory.

Somewhat paradoxically, research 3 has revealed that retrieving information from memory helps students to cement new learning into their long-term memory.

Originally known as the testing effect, retrieving information from memory has a large impact on learning 4 (g = 0.93). Furthemore, it is substantially better 5 than re-studying, reviewing notes and rereading texts.

Retrieval practice includes retrieving both:

The impact of retrieval practice is enhanced when students engage in:

Self-questioning (e.g. why isn’t 9 a prime number?)

Self-verbalising (e.g. talking yourself through the steps in a procedure)

Interestingly, the testing effect is distinct from the impact that feedback has on students’ learning. Put another way, students’ results improve from retrieval practice even when you don’t give them feedback.

While retrieval practice is powerful in its own right, it is even more potent when practice sessions are spaced out over time. Spaced practice involves practising the same thing:

Spaced out over time

This is quite different from practising one thing on Monday and a different thing on Tuesday (or week-by-week). Researchers refer to practising one thing intensely before moving onto the next thing as massed practice. And, research has revealed that, on average, students who space out their practice score 15% higher than students who complete massed practice.

You should always find opportunities to give your students feedback. Giving feedback is both an evidence-based and a high-impact teaching strategy.

But, feedback as a learning strategy has a different twist. It is about your students seeking feedback before receiving it. Research shows that students achieve 42 percentile points better when they regularly seek feedback.

Students can seek feedback from:

People (e.g. you, more able peers, older siblings, parents, tutors)

Material (e.g. textbook exercise answers, online automated scoring services)

When receiving feedback from material, it is important that students go the extra mile and find out why their answers were right or wrong.

Monitoring, or self-monitoring involves actively being aware of when you understand something and when things no longer make sense. Students can monitor their understanding while:

Listening to you

Working on tasks

This simple strategy has a large impact on its own, and is an essential first step for students to know when to ask for help.

After teaching your students to self-monitor, you need to stress the importance of asking for help. The act of asking for help needs little explanation, but your students must understand how much it impacts their learning.

Transforming involves re-outlining or reorganising material. For example, you may have taught your students how to multiply common fractions. In doing so, you may have presented a series of steps.

Your students may have created an outline of these steps and practised following them. Transforming involves your students in reorganising what they have understood a different way.

For example, they could create a Venn diagram comparing multiplication of common fractions with addition of common fractions.

Transforming learned material helps encode learning.

So far, you have read about what types of learning strategies have a high impact on students’ results. You can help your students by teaching them how to use each of these strategies.

But the way you teach them matters too! Research shows that you should:

Explain how, when and why to use each learning strategy (general meta-cognitive knowledge)

Demonstrate how to use each strategy

Scaffold students use of each learning strategy

Offer your students feedback on their attempts (personal meta-cognitive knowledge)

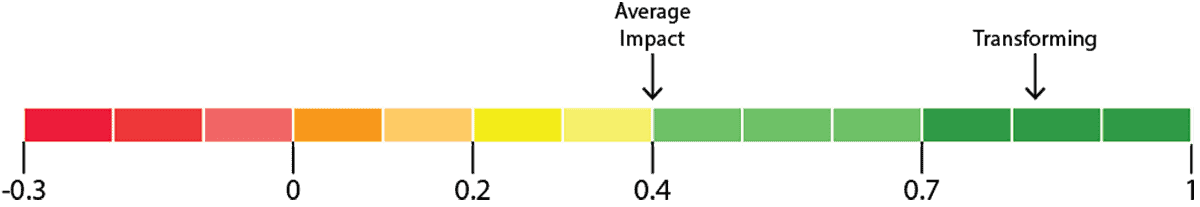

Transforming is the third of our seven learning strategies. As with outlining, transforming involves students in organising information. But when transforming information, students rearrange it in ways that highlight different interrelationships.

These interrelationships can include comparisons, sequences, hierarchies, patterns, trends and cause-effect.

You can transform information in written form using words such as, but, and, next, because, and so. However, transformations usually involve some form of visual structure. For example:

Students need to move information from their short-term, working memories, to their long-term memories. This includes information about things (declarative knowledge) and information about procedures (procedural knowledge).

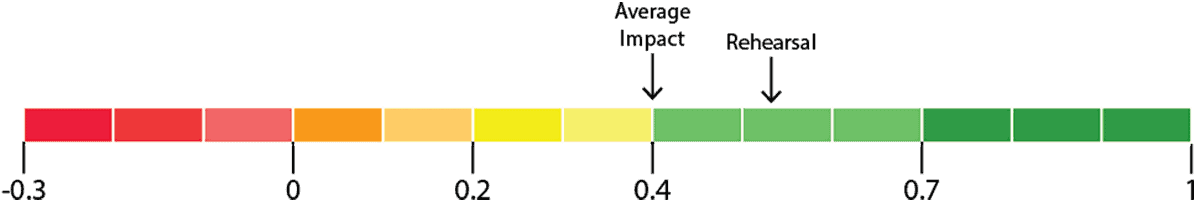

To do this, they should make use of rehearsal and practice. And they form the fourth of our seven learning strategies.

Rehearsal can involve flashcards, mnemonics, chunking, going over past notes, memorising lines for a play, and rereading material.

Practice involves retrieving previously learned information and applying it to the question/task at hand. Retrieval practice works best when students:

One recent meta-analysis found that retrieval practice had an effect size of 0.55 larger than rehearsal.

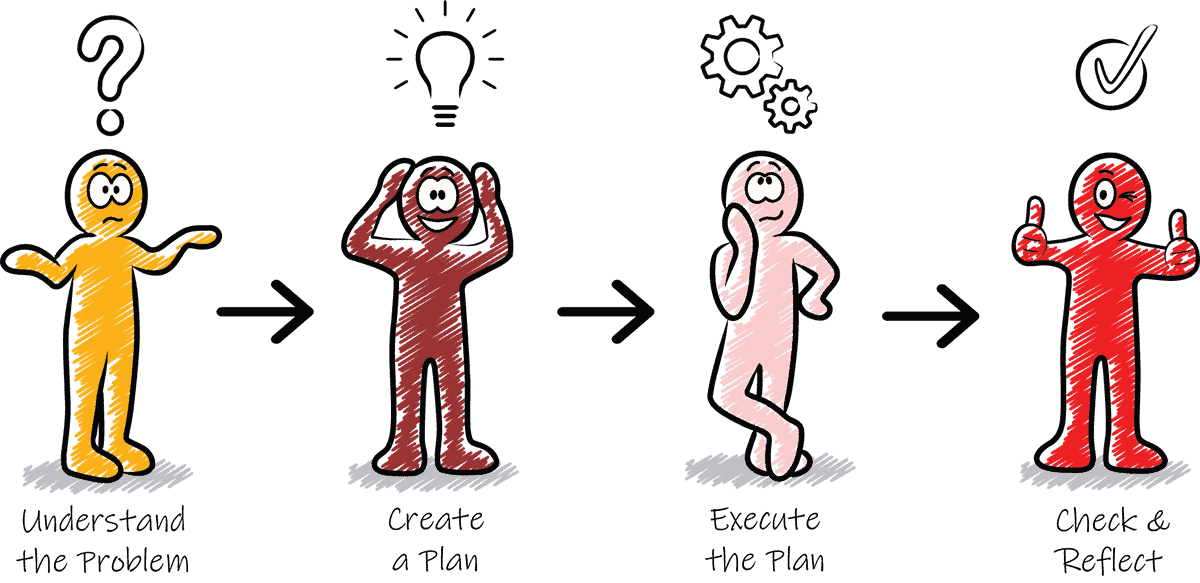

Teaching your students problem-solving skills has a high impact on their results. So, problem-solving makes it in this list of seven potent learning strategies.

This starts with teaching your students the general problem-solving process. There are several different versions of this process, but they are all based on Polya’s 4 steps.

Then, there are specific strategies that you can use within this process. For example, in mathematics, students could use a combination of these strategies:

This one needs little explanation. Students do better when they seek out help from other people, including:

Yet, despite being easy to understand, many students do not do it. Teaching them the importance of seeking help leads to more help-seeking and better results.

You should always find opportunities to give your students feedback. Giving feedback is both an evidence-based and a high-impact teaching strategy.

But, feedback as a learning strategy has a different twist. It is about your students asking for feedback before receiving it. Research shows that students achieve 42 percentile points better when they regularly ask for feedback.

Furthermore, the mindset of students seeking feedback matters too. Students who believe that their performance is the result of their own actions or inactions are more likely to use feedback constructively.

So far, you have read about what types of learning strategies have a high impact on students’ results. You can help your students by teaching them how to use each of these strategies.

But the way you teach them matters too! Research shows that you should:

You can teach your students these core strategies early in the year – e.g. the last teaching period of each day for 5-10 days. And, then show them how to adapt them within different subjects, as part of your teaching throughout the year.